Victor and Eva Ehrenberg

Eva Ehrenberg, née Sommer (1891 Frankfurt am Main - 1973 London) and

Dr. Victor Ehrenberg (1891 Altona - 1976 London)

In case we not only identify Nazi looted property in our library but also find descendants of the owners of these books, the offer of unconditional restitution forms the next step in the process, which we define as "fair and just" in the sense of the Washington Principles. Occasionally, however - as in the case of the Ehrenberg’s here - we receive as feedback from the relatives the wish to leave the book in our library. We are certainly pleased about the trust placed in us, especially since the book is not only in a good place thematically, but also geographically, because the study of this case revealed to us several points of connection of the family to Heidelberg, which can only be briefly mentioned here.

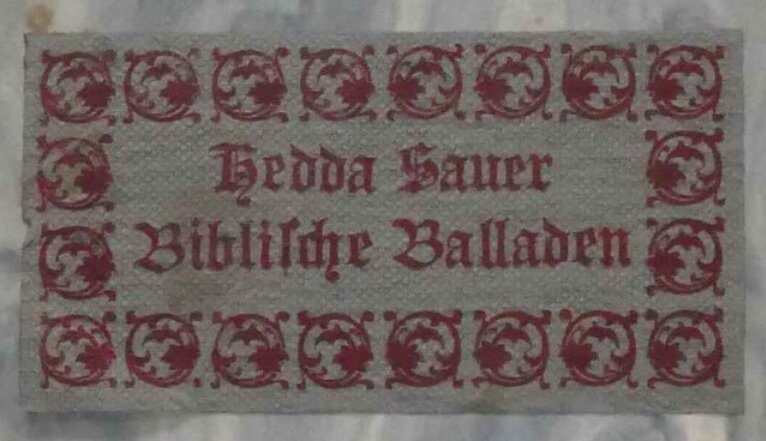

The starting point for the research is the book "Biblische Balladen" (Biblical Ballads) by the author Hedda Sauer, published in 1923 in Liberec/Reichenberg in Bohemia. The traces of provenance contained in it expand the significance of the book beyond its lyrical content to become a meaningful document of contemporary history. As a rule, the person owning the book has a one-sided relationship with the author, since for him the readership remains anonymous. Here, on the other hand, there is a finding with several signs of a direct and personal interaction, at least we dare to interpret it that way: the author herself is in direct relationship with the persons mentioned in the two bookplates and she is the author of the dedication inserted by hand.

Hedda Sauer was born Hedvika Rzach in Prague in 1875. Her parents Hedvika Rzach, née Polak and Dr. Alois Rzach - classical philologist and Semitist at the Prague University, favored Hedda's literary interest early on. At a young age she married Dr. August Sauer, a Viennese who had just been appointed to the chair of German language and literature in Prague. Three years after the marriage, Hedda Sauer published her first volume of poetry. In addition to her own creations, she also emerged as a reviewer of lyrical works and published mainly in daily newspapers and periodicals on contemporary literature. In the Prague "Club of German Women Artists", constituted in 1906, we find her listed as the founding chairwoman.

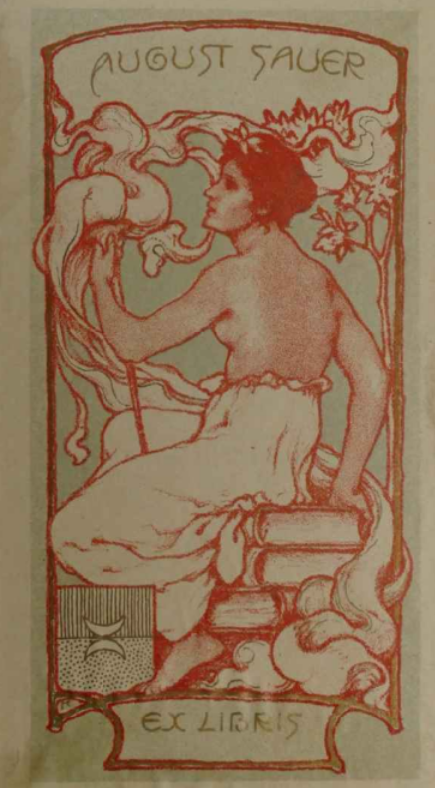

After Hedda Sauer published the "Biblische Balladen" in 1923, she gave a copy to her husband - at least that is what we can surmise, since his bookplate is on the inside of the book cover. It shows a female semi-nude sitting on books in the manner of Art Nouveau as well as a kind of coat of arms with a mirrored crescent moon. There is also a bookplate by August Sauer, which was certainly made earlier and which clearly shows the identical symbolism as part of a (family?) coat of arms. We would be grateful for any information about this. The painter Karel/Karl Kostial, born in 1878 in Vrchlabí/Hohenelbe, educated in Munich and working in Prague, was probably the artist of our bookplate.

August Sauer died in Prague in 1926. Therefore, the bookplate was probably placed in the book between 1923, the year of publication of the book, and 1926, the year of Sauer's death.

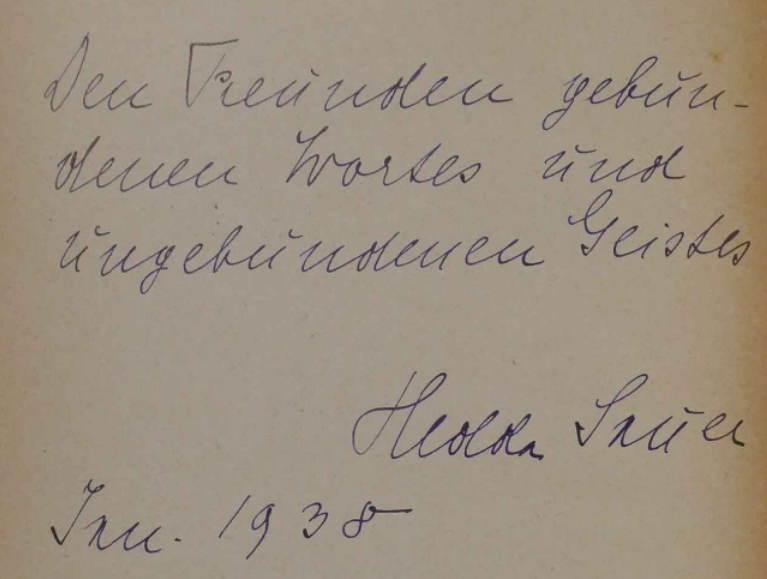

Three years later, the classical philologist Dr. Victor Ehrenberg received a call to the University of Prague. Last active as a lecturer in Frankfurt am Main, he changed his place of work and moved with his wife Eva, née Sommer and their two sons to the Vltava. The other provenance references in the book suggest a good contact between the Ehrenberg’s and the widow Hedda Sauer. Prague's German-language academic orbit was manageable in those years anyway - Hedda's father Alois Rzach, who died in 1935, continued to lecture until his death and certainly had contact with Victor Ehrenberg - but Eva Ehrenberg and Hedda Sauer also shared a penchant for poetry. Whether Hedda Sauer's handwritten dedication was only to Eva Ehrenberg or to the couple, we can only guess

Den Freunden gebundenen Wortes und ungebundenen Geistes

[To the friends of bound word and unbound spirit]

Hedda Sauer

Jan. 1938

The search for the origin of this very aesthetic imagery leads us to the ancient historian Ernst Curtius, who had used this metaphor in a slightly different form during a speech at Göttingen University in 1857. We can assume that the quotation was not unknown in the relevant circles, especially since Victor Ehrenberg had also completed part of his studies in Göttingen - albeit much later.

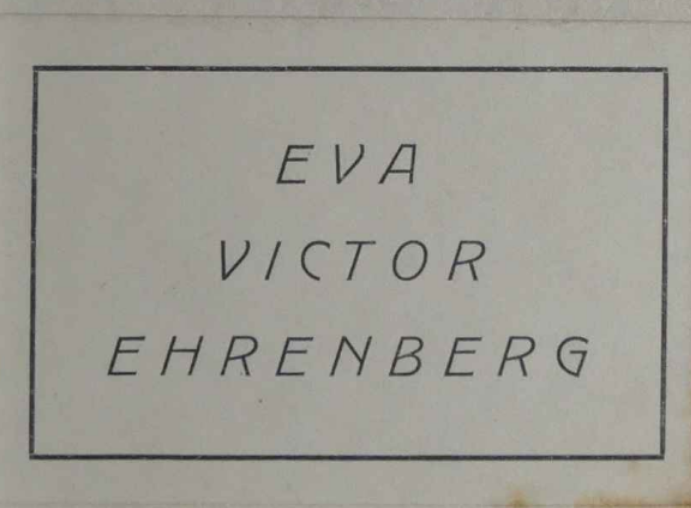

Because of the use of the plural in the dedication we can assume that the book was jointly intended for the Ehrenberg couple, and this also explains the bookplate that was now fixed under that of the late August Sauer:

Eva

Victor

Ehrenberg

Eva Ehrenberg was born Eva Emilie Dorothea Sommer, daughter of Klara Helene Sommer, née Edinger, and the lawyer Dr. Siegfried Sommer in Frankfurt am Main in 1891. In 1904, the family moved to Kassel, where Eva's father assumed the office of Oberlandesgerichtsrat. He was the first Jewish civil servant in the Prussian state to hold this position. The promotion was the result of an initiative by Wilhelm II, with whom Sommer had attended the Kassel Gymnasium together in the 1870s and had become friends. In Kassel, Eva also met Victor Ehrenberg, whom she married in 1919. During the preceding war years, Eva became involved in war welfare and wrote patriotic poems. Most of her literary work is available only in unpublished manuscripts. Like Hedda Sauer, she was introduced to literature at a young age. After Eva reached the age of ten, her mother inspired her with the works of Dante, Goethe, Shakespeare, Nietzsche, and J.P. Jacobsen.

Victor Ehrenberg was born in Altona in 1891, the youngest of three brothers. Soon after, the children moved to Kassel with their parents Gabriela Emilie Ehrenberg, née Fischel, and Otto Ehrenberg. After Victor graduated from school, he decided to study architecture in Stuttgart, but soon moved first to Göttingen and then to Berlin, and there, after the encouragement of his brother Hans Ehrenberg, he turned to classical studies and classical philology. (Hans Ehrenberg, Victor's oldest brother, studied law and philosophy, converted to Protestantism and was a private lecturer in philosophy at the University of Heidelberg from 1910; he was active in the local SPD and played a formative role in the so-called Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche). He emigrated to England in 1939 and returned to Germany after the war, since 1953 again in Heidelberg until his death in 1958.) In 1914 Victor Ehrenberg went to war and an extensive correspondence with the Berlin historian and his mentor Eduard Meyer provides information about his experiences on the Western Front. Victor Ehrenberg was wounded at least twice, and his initially enthusiastic attitude toward Germany's military agitations became increasingly critical as the war progressed.

After the end of the war, Ehrenberg continued his studies in Tübingen. In 1919 Eva Sommer and Victor Ehrenberg were married in Frankfurt am Main. Franz Rosenzweig gave a speech on the occasion, which has also been handed down - Rosenzweig was Victor Ehrenberg's second cousin, or the pedagogue Samuel Meyer Ehrenberg their common great-grandfather. Victor Ehrenberg received his doctorate in 1920 in Tübingen and habilitated two years later in Frankfurt am Main, where he was a private lecturer in ancient history. In 1928 he became extraordinarius, but already one year later he accepted the offer to take over the chair of ancient history and epigraphy at the German University in Prague of Heinrich Swoboda, who died in 1926. The new center of life was not a white spot on the map for Victor Ehrenberg, because his mother, Emilie Ehrenberg, was a native of Prague (and a cousin of both Leontine Goldschmidt, née Porges Edle von Portheim and a cousin of Leontine's husband Victor Goldschmidt, both of whom worked in Heidelberg and their heritage is still present in the city).

In the 1930s, the Ehrenbergs were increasingly confronted with their Jewish origins, which played almost no role in their private lives. The publishing houses in the German Reich refused to allow Victor Ehrenberg to publish his studies, and the children Gottfried (b. 1921) and Ludwig (b. 1923) also felt increased hostility in Prague. At the latest with the so-called Munich Agreement and the “Gleichschaltung” of the German University as well as the German high schools, a future in Czechoslovakia was out of the question for the family. In 1938, Victor Ehrenberg had met British colleagues at a Zurich historians' congress, who supported the Ehrenberg’s and organized an invitation to England. About four weeks before the German troops entered Prague, the family was able to emigrate, equipped with all the necessary papers. Eva Ehrenberg later reflected on the situation at the Prague train station: "In a nonstop effort we had made the race; we got out before Hitler came in."

The new start in England was initially difficult, but despite appointments at various German universities, Victor Ehrenberg could no longer consider continuing his teaching activities in Germany. He only returned to his homeland briefly as a guest speaker or conference participant (in 1955, for example, he seems to have given a lecture at the Heidelberg Historical Seminar; in 1958 he became a member of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences).

The exact circumstances of the book's removal from the family's possession are unclear, but the fact that it came from a context in which masses of looted books had been gathered in Prague suggests that the Ehrenberg’s had to leave it behind involuntarily.

Excursus: Dr. Adolf Grohmann and the Reinhard Heydrich Foundation

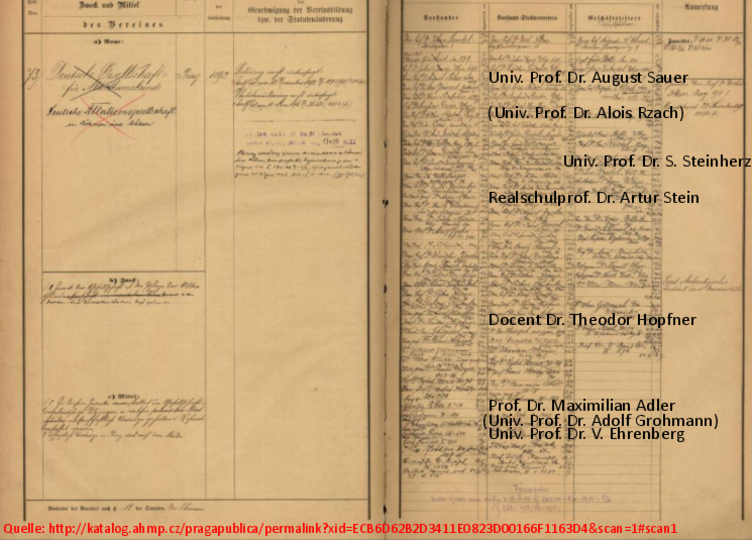

For the books from the Emil Davidovič estate, it has so far been possible to define a wide variety of withdrawal contexts. These include, for example, the incorporation of books from different sites into the Terezín libraries or into the Prague "Jewish Central Museum". For the books from the environment of the Prague classical scholars, a new context may possibly open up, but we are still in the realm of conjecture. The reason for this is the "Deutsche Gesellschaft für Alterthumskunde" (later "Deutsche Altertumsgesellschaft in Böhmen und Mähren"), founded in 1892. In the corresponding entry of the Prague society cadastre we find the names of the board members, their deputies and the secretaries listed until 1937. Some of these mentioned persons, who certainly knew each other more or less well, we also find as owners of books in the stock we examined: Dr. Victor Ehrenberg, Dr. Samuel Steinherz, Dr. Arthur Stein, Dr. Theodor Hopfner as well as Dr. Maximilian Adler. From Adler's holdings, our library has a volume of manuscripts that has not yet been processed. He probably deposited the material in Prague before his deportation to Theresienstadt, either in the Jewish Museum or in the Oriental Institute of Prague University. Hopfner replaced the deposed Adler in 1940 and, as a non-Jew, was not affected by German racial laws, but he did not have a good standing with the National Socialist authorities ("Professor Hopfner is not to deal again in his work with matters similar to those in his last paper, “Das Sexualleben der Griechen und Römer”. For the time being, his official emoluments remain unchanged.").

The Arabist Dr. Adolf Grohmann also appears in the list of the association as a member of the board. He had taught Semitic philology at Prague University since the 1920s. The “Gleichschaltung” of the university landscape in the "Protectorate" favored the course of Grohmann's academic career, not least due to the dismissal of the Jewish teaching staff. In the fall of 1941, he received a permanent position and was appointed director of the Seminar for Semitic Philology and Islamic Studies. Prior to this, there had already been efforts to establish an "Institute for the Study of the History of Judaism in Bohemia and Moravia" in Prague, which was to be affiliated with the planned "Working Group for South and Southeast Research and the Cultivation of Oriental Studies at the German Charles University." Grohmann was assigned a decisive role in this. For this purpose and to build up a specialized library, Grohmann traveled to Moravian Ostrava in March 1941 to take a look at a "Jewish library of about 4000 volumes" there. Little is yet known about the incorporation of expropriated library holdings into the “gleichgeschaltet” research institutions. Actions of this kind were also due to the "commitment" of individuals, which we can also attribute to Grohmann. The hitherto little matured efforts to establish a new scientific foundation in the sense of the Nazi ideology received a further impulse as well as a namesake after the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in Prague in May 1942. Several institutes at Prague University formed the intersection between the established teaching and research based there and the Reinhard Heydrich Foundation itself as a space for further politically directed, or politically exploitable, research focusing on racial and folkloric aspects. As head of the Oriental Institute attached to it, Grohmann may have used his connections to the former faculty to obtain the desired book material, by whatever means. Perhaps he had requested the books for his institute directly, perhaps they had been given to the institute by the owners on a not entirely voluntary basis. The dynamics of the book transfers shortly before and shortly after 1945 around Prague are still very opaque, also with regard to the interactions between the university institutions and the Jewish Community, or the Jewish Museum. There is still considerable need for clarification here.

Acknowledgements

For contacting the descendants, we sincerely thank Anne Webber of the Commission for Looted Art. For research on the Ehrenberg’s, we are assisted by the staff of the Leo Baeck Institute New York, the Archives of the Charles University in Prague, the Archives of the University of Heidelberg, and the Landeskirchliches Archiv of the Evangelical Church of Westphalia in Bielefeld.

Selected literature

Audring, Gert. U.a. (Hg.): Eduard Meyer. Victor Ehrenberg. Ein Briefwechsel 1914-1930, Berlin und Stuttgart 1990.

Brocke, Michael (Hg.): Becherrede zur Hochzeit von Viktor Ehrenberg und Eva Sommer [gehalten von Franz Rosenzweig] / Eva Ehrenberg: Der Jugend in Deutschland 1960. Eine nie gehaltene Ansprache [Auszug aus Ehrenberg, Eva: Sehnsucht, s.u.], in: Kalonymos 16 (2013), Heft 2, S. 1-5.

Ehrenberg, Eva: Sehnsucht - mein geliebtes Kind. Bekenntnisse u. Erinnerungen, Frankfurt am Main 1963.

Ehrenberg, Hans P.: Autobiography of a German Pastor, London [1943].

Ellinger, Ekkehard: Deutsche Orientalistik zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933-1945, Edingen-Neckarhausen 2006.

Curtius, Ernst: Göttinger Festreden, Berlin 1864 [das der o.g. Widmung möglicherweise zugrunde liegende Zitat befindet sich auf S. 36f.], https://gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de/id/PPN637443330.

Kisser, Nelli: Victor Ehrenberg und Frankfurt, in: Färber, Roland und Fabian Link (Hg.): Die Altertumswissenschaften an der Universität Frankfurt 1914–1950 - Studien und Dokumente, Basel 2019, S. 73-87 [darin auch weiterführende Literatur/Quellen].

Oliva, Pavel und Jan Burian: Die Prager Altertumswissenschaft und soziale Probleme der Antike, in: Klio 71 (1989) 2, 477-486. (https://www.proquest.com/docview/1305199123/fulltextPDF/D6E7630E731F4D2APQ/5?accountid=11359).

Petr Hlaváček & Dušan Radovanovič. Hrsg von Erhard Roy Wiehn: Verdrängte Elite. aus dem Gedächtnis verbannte Gelehrte der Deutschen Universität in Prag, Konstanz 2013, S. 79f.

Rebenich, Stefan: Altertumswissenschaften zwischen Kaltem Krieg und Studentenrevolution. Zur Geschichte der Mommsen-Gesellschaft von 1950 bis 1968, in Hermes. Zeitschrift für Klassische Philologie, Bd. 143, H. 3, 2015, S. 257-287. (https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/3656/1/Rebenich_Altertumswissenschaften_2015.pdf).

Scholz, Peter: Die „Alte Geschichte“ an der Universität Frankfurt 1941-1955, in: Marlene Herfort-Koch, Ursula Mandel, Ulrich Schädler (Hg.), Begegnungen. Frankfurt und die Antike 1, Frankfurt am Main 1994, S. 441-464 (https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/4317/1/Scholz_Die_alte_Geschichte_an_der_Uni_Frankfurt_1994.pdf).

Vogt, Joseph: Victor Ehrenberg, in Gnomon 48 (1976), H. 4, S. 423-426 [Nachruf, digital via JSTOR].

Selected sources

Bundesarchiv, Personalakte Dr. Adolf Grohmann, BArch R 31/548; Personalakte Dr. Theodor Hopfner, BArch R 31/562

Landeskirchliches Archiv der Evangelischen Kirche von Westfalen, 7 Briefe von Hans Ehrenberg an seinen Bruder Victor (1928-1936), Signatur 3.17 / Ehrenberg, Hans; Pfarrer, Nr. 25

Leo Baeck-Institute New York, Franz Rosenzweig Collection (AR 3001), Series IV: Family, 1832-1966, Rosenzweig-Ehrenberg Family, https://archives.cjh.org/repositories/5/archival_objects/829855

Leo Baeck-Institute New York, Research Foundation for Jewish Immigration, Personal files of Jewish Refugees, MF 540, [Eva Ehrenberg], https://archive.org/details/researchfoundati14rese/page/n555/mode/1up, [Victor Ehrenberg], https://archive.org/details/researchfoundati14rese/page/n593/mode/1up

Leo Baeck-Institute New York, Eva Ehrenberg Collection AR 3664 [Gedichte], https://archive.org/details/evaehrenbergf001/mode/1up?view=theater

Ancestry.de, Geburtsurkunde Victor Leopold Ehrenberg, Verlust- und Verletztenlisten des 1. Weltkriegs [Victor Ehrenberg], Heiratsurkunde Eva Sommer und Victor Ehrenberg

University of Sussex Library, German Jewish Family Archive, Signatur SxMs96: The Elton/Ehrenberg Family Papers (1819 - 2001), davon sind online verfügbar: Victor Ehrenberg's WWI album, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28433300 und die Becherrede [von Franz Rosenzweig] zur Hochzeit von Viktor Ehrenberg und Eva Sommer, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28433299, zur Sammlung allgemein siehe auch https://www.sussex.ac.uk/library//speccoll/cgjs/archive/elton_intro.shtml

University Archives, The University of London, Institute of Classical Studies, Victor Ehrenberg Papers 1913-1976, https://archives.libraries.london.ac.uk/Details/archive/110018901

Bericht über die Jahres-Hauptversammlung der „Deutschen Gesellschaft für Altertumskunde“, darunter ein Vortrag von Victor Ehrenberg („Panhellenentum bei Homer“), Prager Tagblatt Nr. 258 vom 5.11.1929, S. 6, https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=ptb&datum=19291105&seite=6&zoom=33

Eintrag im Prager Adressbuch von 1937/38, „Ehrenberg Viktor Dr. univ. prof. m. Eva Stresovice Slunná 7, t 72717“, https://www.digitalniknihovna.cz/mlp/view/uuid:c6e779e0-7e5d-11dd-a117-000d606f5dc6?page=uuid:f8e13010-7dab-11dd-a4e3-000d606f5dc6&fulltext=ehrenberg

Carlebach, Joseph: Franz Rosenzweigs philosophisches Lebenswerk, Der Israelit 75, Heft 30 vom 26.07.1934, S. 11, [Ehrenbergs Einfluss auf Rosenzweig] https://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/cm/periodical/pageview/2538435

Stadtarchiv Prag, Vereinskataster, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Alterthumskunde, Signatur IX/0073, http://katalog.ahmp.cz/pragapublica/permalink?xid=ECB6D62B2D3411E0823D00166F1163D4&scan=1#scan1

Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen, Hessische Biografie, Ehrenberg, Victor Leopold https://www.lagis-hessen.de/pnd/118681729

Archiv der American Guild for Cultural German Freedom, Deutsches Exilarchiv 1933-1945 (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek), Personalakte Victor Ehrenberg [darunter auch ein Lebenslauf], https://d-nb.info/dnbn/1278097074

„Bekanntmachung… über die Einziehung von Vermögen im Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren…“ [Familie Ehrenberg in Prag], Deutscher Reichsanzeiger und Preußischer Staatsanzeiger Nr. 164 vom 16.07.1942, https://digi.bib.uni-mannheim.de/viewer/reichsanzeiger/film/041-8482/0360.jp2

Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften, Unsere Mitglieder [Victor Ehrenberg], https://www.hadw-bw.de/mitglieder?id=702

Ankündigung eines Vortrags („Die Anfänge unserer Schrift“) Victor Ehrenbergs im tschechoslowakischen Rundfunk, Pilsener Tagblatt 38 vom 12.11.1937, Nr. 260, S. 6, https://www.difmoe.eu/view/uuid:f1d00d96-c307-4069-9c7a-5281bce17650

Nachruf Eva Ehrenberg, AJR Information, October 1973, S. 10 [Association for Jewish Refugees in Great Britain], https://ajr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/1973_october.pdf

[Text: Ph. Zschommler]